“Max Reinhardt saw... the commedia dell’arte as one of the most important roots of modern theater.” Reinhardt’s fondness for Italian art of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries was well known, with Leopoldskron being the best example of this.

The Venetian Room takes its name from the panels on the wall, depicting scenes of Commedia dell’arte (“Comedy of professional artists”), an influential form of traveling and improvisational theatre that originated in Italy in the 16th century. The panels are generally regarded to be 18th-century copies of paintings originally by Jean-Antoine Watteau (1684-1721). Reinhardt greatly admired Commedia dell’arte and the paintings were a major source of inspiration for his theatrical works, including promenade performances he staged in Schloss Leopoldskron. He installed the wall panels during renovations to the Schloss in 1930 after he acquired them from Italy. During Reinhardt’s time, the Venetian Room was used as his music parlor.

The gilded panels served as inspiration for the set design of the ballroom in the Von Trapp family manor in the 1965 Oscar-winning musical, The Sound of Music.

Commedia dell'arte

The theatrical art form Commedia dell’arte developed at a time when Venice was the center of cultural exchange and development. According to Commedia expert Didi Hopkins, “artists were repositioning their ideas about who they were in relationship to the world because the planet was being discovered in a new way. Commedia came from that backdrop of curiosity.” This repositioning drew on the long tradition of masks in Venice that facilitated becoming someone other than oneself and rebirth in line with the larger renaissance movement. Hopkins also notes that the Commedia revolutionized and democratized theater performance, symbolizing every individual’s value to be part of humanity and tell his or her story.

The baroque improvisational theater of the commedia dell’arte was an art form beloved by Max Reinhardt. This passion was kindled in his Viennese childhood by the city’s street singers and the popular Hanswurst theater.

“As a child, he still heard the calls of the street vendors, whether they were lavender women, rag collectors, knife grinders, chestnut roasters or sausage sellers. There was hardly a courtyard in which the wheezing sounds of an old barrel organ did not ring out. The folk singers, in whom the art of improvisational comedy lived on, were unique.”

“The memory of this last incarnation of the commedia dell’arte stayed with him for the rest of his life.”

In the commedia dell’arte, the stage action is characterized by stock characters and their masks, which Reinhardt also used in some of his productions. “As can be seen from his director’s notes …, Reinhardt’s fundamental idea was to synthesize all the elements of comedic theater—acting, words, music, dance, apparent improvisation and pantomime—into a complete work of art.”

Reinhardt collected valuable pictures, figures and books, and brought them to Leopoldskron.

Created in the 1920s, the Venetian Salon is regarded as one of Max Reinhardt’s masterpieces. The Venetian Salon was originally the music room, complete with a red lacquered Steinway grand piano. Reinhardt’s first theater and commedia dell’arte images were embedded in the stucco of this room, while figurines of dancers, jugglers and comedians stood on consoles.

The painting by the Venetian painter Pietro Longhi (1702–1785) was gifted to Reinhardt in 1928 by the actress Lillian Gish (1893–1993), after she worked on his never-completed film about Therese of Konnersreuth. Wonderful Harlequin portraits were given to Reinhardt by the writer Richard Beer-Hofmann (1866–1945).

The stucco borders on the ceiling and the corner fireplace originate from the 18th century. In 1929, Reinhardt fulfilled a personal dream by purchasing original Venetian panels, wallpaper and mirrors. The wood and mirror installations on the walls originally came from an Italian palazzo, Reinhardt having acquired them at an auction in Berlin. Salzburg cabinetmakers later placed these works in the room together with valuable pieces from Reinhardt’s private commedia dell’arte collection. Adding these to the room called for a tremendous level of craftsmanship from Anton Widerin. Reinhardt’s ever-growing collection of precious artworks was precisely integrated into the room by the fall of 1930. One of the historical polished mirrors was broken by Widerin's brother Guido and had to be replaced by the Lobmeyr company in Vienna. Widerin kept precise records of the work done, as a keepsake of and testament to his great expertise.

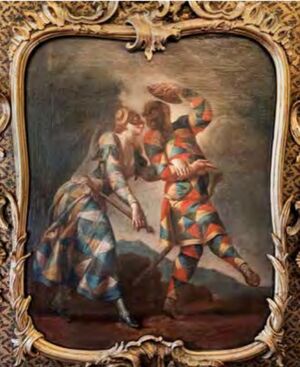

Most of the 35 oil paintings have no signatures or dates. “This does not detract, however, from the appeal of the pictures. They radiate joie de vivre, comedy and sensuality. … Arlecchino and Columbina, Dottore and Pantalone, Capitano and Zerbinetta, Pantalone following paths of love despite his ailments, and Harlequin again and again. Strikingly, there are no fight scenes; instead, joviality and cheerfulness dominate.”

The figure of harlequin in the typical patchwork costume had mythological-demonic origins in medieval customs, embodying the troublemaker, the rogue or the cheeky moralist. Spectators interpreted his black half-mask or black-colored face as an indication of dishonest intentions. Norms of previous centuries meant that this depiction was viewed humorously and socially acceptable. This form of costuming continued to appear across eras. For us in the 21st century this costume is widely deemed as “Blackface” and thus racist (Read more: Venetian Salon Protest).

On the wall next to the chimney, there is the copy of “Harlequin, Pierrot and Scapin,” a triptych by Jean-Antoine Watteau (1684–1721), which was produced in 1716–18. This work quickly generated great enthusiasm and was therefore copied many times, beginning very soon after its creation. The excellent copy in the Venetian Salon was probably painted directly from the original.

The remaining paintings depict commedia dell’arte characters as well as five landscapes. Fifteen flower motifs were painted by Gusti Adler’s sister Marianne.

Reinhardt’s favorite pieces, however, were the sixteen paintings discovered by Gusti Adler in Rome in 1930. Just as the famous Milan opera house, La Scala, was about to buy them, Reinhardt acquired them for the then enormous sum of 54,000 lire. They were then hung in a large hall in Leopoldskron.

“Of all his paintings, he loved the Ferrettis the most. This largest completed series of commedia dell’arte paintings was a constant source of inspiration and aesthetic delight for him. He didn’t even know … at the time that the sixteen unsigned paintings were by Giovanni Domenico Ferretti. The antiquarian who sold them attributed the paintings to the Venetian [painter Domenico] Maggiotto.”

Reinhardt had the paintings sent to him in Hollywood in 1938, then later to Santa Monica, California. Today they hang in the John and Mable Ringling Museum in Sarasota, Florida. The museum experts in Florida were the first to clarify the artist’s identity beyond doubt and named the series “The Mishaps of Harlequin”, painted between 1740 and 1760.

In 1950, Gottfried Reinhardt sold fifteen of the sixteen paintings to the Ringling. They have been restored to a great degree and impress the viewer with the luminosity of their colors.

The sixteenth painting (“Harlequin as Paterfamilias”) was acquired in 2012.

Even the artfully designed wooden floorboards were created by Reinhardt. His attention to detail is demonstrated in the pattern of the floor, which reflects the harlequin costumes. However, during the installation Reinhardt realized that he could not afford the floor in the design originally conceived, wich meant some improvisation was required. Reinhardt had normal wooden plank flooring laid in the center of the room, which he simply covered with a carpet – just as we still do now.

The charm exuded by the Venetian Room is primarily down to the wonderful candle chandelier on the ceiling. With mirror installations reflecting the candlelight, this room is perfect for romantic candlelit dinners (even if real candles are no longer permitted for fire safety reasons and now substituted by modern LED candles).

75 Years in 12 Vignettes

With 75 years behind us and more than 40,000 Fellows in 170 countries, Salzburg Global obviously has many stories to tell. The following 12 vignettes have been selected not only for their ability to relate the history of the institution, but also to convey the unlikely symbiosis of a visionary enterprise, conceived at an American university that came to be situated in an eighteenth-century rococo palace in the heart of Europe with the goal of serving the global good.