To the casual observer, Schloss Leopoldskron looks compact, strongly contoured and rigorously structured. This can be put down to its basic shape: an almost perfect cuboid. The rich decoration of the facade and the flowing forms of the central avant-corps stand in clear contrast to this. This juxtaposition and the way the palace is harmoniously embedded in the surrounding countryside are what makes Leopoldskron so special.

The palace is aligned with the Untersberg massif, which stands opposite. Depending on the angle of observation, the Leopoldskroner Weiher offers a reflection of the silhouette of the Alps around Berchtesgaden or the facade of the palace.

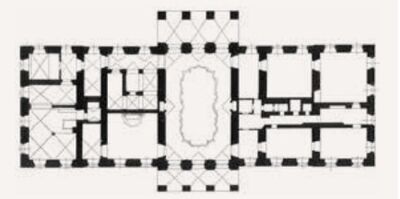

The central section of the palace is primarily used for gatherings of people: from the large reception hall on the ground floor, a staircase on the side leads to the banquet hall, a two-story room bathed in light. Above it is the gallery, an event room with the same footprint but a lower ceiling. The “Painters’ Gallery” of Count Franz Laktanz Firmian (1709–1786) was housed here in the 18th century.

The chapel and the staircase are adjoined to each other in the west wing of the palace. The upper floors of both wings contain living quarters and hotel suites. The grand ceremonial rooms on the bel étage can be accessed from the staircase via a series of enfilades. This also used to be the case on the upper floors, which were later modified. Baroque cocklestoves stand in the inner corners of the rooms, which were fueled from windowless heating passages. On the second floor, galleries run along the windows on both sides of the banquet hall, connecting the west and east wings.

The two main facades of the palace are designed in the same way. Parallel joints on the first floor and three cornices partition the facade horizontally. The entablature that prominently projects outward above the third floor clearly demarcates the simple mezzanine floor above. Another cornice and a narrow fascia complete the building. The flanking wings of the facade with their five window axes are modestly designed. The side avant-corps only stand out a little and are lightly accentuated by pilaster strips and more elaborate eaves on the first floor.

In the northwest and southeast, the two entrances to the building are fronted by projecting balconies with round arches, which are supported by four robust pillars and topped with a marble balustrade. The central avant-corps of the facade rises above the balconies with three window axes. Four marble pilasters with a composite capital join the second and third floors together. The window moldings and the curved marble ledges emphasize the vertical thrust. The gable is framed by two flanking volutes. Above it, a stucco cartouche with a coat of arms and a metal crown serve as symbols of the Firmian family. The distinctly profiled cornices of the final round give prominence to the coat of arms.

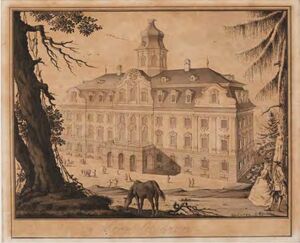

In 1740, the Salzburg court gardener and architect Franz Anton Danreiter (1695–1760) made an artistic rendering of the palace from plans. This shows the palace with a mansard roof and a turret. In later illustrations, however, the palace is seen in its current form without a mansard or turret. It is unclear whether these parts of the building were erected at all, or whether they were erected and later demolished.

The Commissioning and Building of Leopoldskron

The Salzburg archbishops Count Johann Ernst Thun (ruled 1687–1709) and Count Franz Anton Harrach (ruled 1709–1727) had brought the most respected architects of the Viennese court and high nobility to Salzburg: Johann Bernhard Fischer von Erlach worked for Archbishop Johann Ernst for 15 years, giving Salzburg its baroque skyline. Lukas von Hildebrandt was the favorite architect of the Harrach family in Vienna. He built the Upper Belvedere Palace for Prince Eugene in Vienna and, at the same time, constructed Schloss Mirabell in Salzburg from 1721 to 1727.

Archbishop Leopold Anton Firmian (ruled 1727–1744) did not follow the example of his two predecessors. He entrusted the design of Schloss Leopoldskron to the young aristocrat and Scottish Benedictine monk Bernard Stuart, even though Stuart had no knowledge of architecture. How was this possible?

Bernard Stuart was educated at the Benedictine monastery of St. James in Regensburg (also known in English as the Scots Monastery), which he attended for ten years from the age of 12. His schooling was rooted in the “seven liberal arts” and built the foundations of Stuart’s knowledge of applied arithmetic, geometry and astronomy. Thomas Placidus Fleming (1642–1720), the abbot of St. James, had a special connection with these subjects because he had served as an officer in the Royal Navy and had mastered them on his own. After two years of theological studies at St. James, Stuart came to Salzburg in 1728 or 1730 as a chaplain of the Benedictine monastery in Nonnberg, and was appointed to a professorship in mathematics at the University of Salzburg in 1733.

Schloss Mirabell, the Model for Schloss Leopoldskron

When drawing up plans for Leopoldskron, Stuart was surely able to draw on the extensive knowledge of Friedrich Koch (ca. 1673–1736), the head architect at the princely court. Koch had previously built Schloss Mirabell according to plans designed by Lukas von Hildebrandt. A comparison of the Mirabell and Leopoldskron palaces also suggest that Stuart was directed to use Schloss Mirabell as a model. Firmian was thus able to entirely satisfy the prevailing aesthetic expectations of the nobility and clearly emphasize the high social status of his family both within the archbishopric of Salzburg and the wider Austro-Habsburg cultural sphere.

The exterior facade of the east wing of Schloss Mirabell was used—in modified form—as a model for the construction of the two main facades of Leopoldskron: huge pilasters connect the first and second floors of both buildings. In place of a tower, the vertical structure of Leopoldskron is accentuated by the three-axis central avant-corps with its additional gabled story. The horizontal effect of large corner wings was dispensed with in Leopoldskron. Instead, side avant-corps with two axes and superimposed baroque gables were constructed.

The central positioning of the reception hall and the Marble Hall (or banquet hall) as well as important design elements of the staircase were inspired by the garden wing of Schloss Mirabell. The exterior facade of the garden wing of Schloss Mirabell had a decisive influence on the movable window frames and window aprons of the facades in Leopoldskron. Inside the building, the original baroque appearance of the reception hall, the chapel, the staircase, and the banquet hall has been largely preserved.

Important Rebuilding Episodes in the Palace’s History

Throughout its history, the palace was adapted to the needs of its various owners. Max Reinhardt renovated the basement, floors and roof, “as well as having heating and cold storage installed.” The ceremonial rooms on the first floor were remodeled in 1926 and 1927.

After purchasing the palace, Salzburg Global Seminar undertook a comprehensive renovation of Leopoldskron between 1959 and 1962, in order to preserve the historic structure, revive the facade and parts of the interior décor, and make the building usable all year round. An elevator was installed in the east wing, and student apartments were added on the third floor (the bathrooms of which were renovated in 1991). Nine existing suites in the east wing, five of them on the third floor, were remodeled in line with modern standards in 2017. “Inconvenient older fixtures were removed and the rooms were largely restored to their earlier baroque geometry."

Stylistic Classification

The architectural form of Schloss Leopoldskron in Salzburg is characterized by two design features:

- A very compact exterior form

- And an internal spatial design that has been completely optimized in terms of form and function.

Schloss Leopoldskron therefore follows classical rather than baroque design principles. These are: clarity and detailed hierarchical structuring of all load-bearing elements; harmony and balance with regards to volume; right-angled orientation of straight lines and restrained décor. These features are very much in keeping with the rigor, discipline and determination of the client.